It’s Spring in the northern hemisphere and, for many, that marks the beginning of sewing season (#memademay, for reference). So this week, a salty little sewing tale…

In the 1860s, a small but impassioned debate broke out in both England, France, and the U.S. regarding the potentially “exciting” effects of the sewing machine. That’s right—doctors worried that the rhythmic pumping of the thighs resulted in sexual arousal and that women workers were using the machines to stimulate themselves. Equal parts hilarious and infuriating, it is a story that brings up questions of the industrial use of women’s bodies, their unanswered complaints of fatigue and ailment, masculine control of female sexual processes, and the threat of a working woman enjoying a private pleasure. In short, it’s a juicy one. (Pun most definitely intended.)

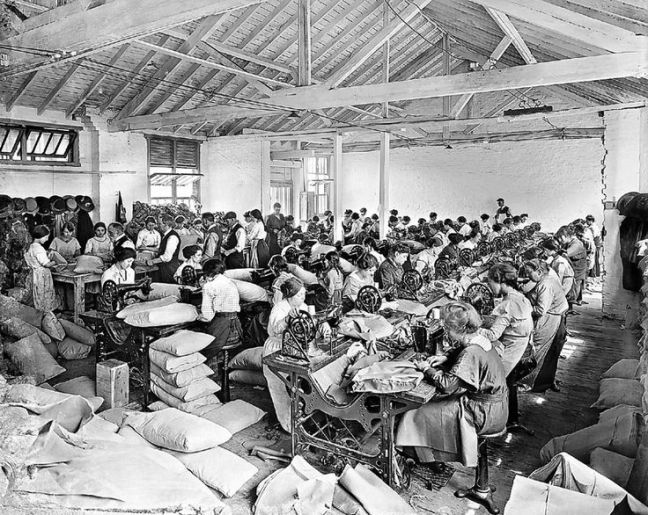

A New Era

Our current movements toward Slow Fashion, transparency, and #WhoMadeMyClothes draw attention to the plight of garment workers, often in places far removed from the centers of fashion and consumption. In these places, conditions and demands are not unlike those exacted upon the very first textile workers in 19th-century Europe and the United States. Thomas Hood’s 1843 poem “Song of the Shirt” lyrically details the grim conditions and consequent psychological state of industrial seamstresses, and its publication in Punch magazine (the closest thing 19th-century readers would have had to social media) helped lead to awareness and improved conditions for some of these workers.

Work — work — work,

Till the brain begins to swim;

Work — work — work,

Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

And sew them on in a dream!

The deplorable labor conditions for 19th-century garment workers are well documented: men, women, and children of the lower classes risked short- and long-term bodily harm in exchange for long hours and meager wages. At the same time, the textile boom led to a kind of liberation: women were able, for the first time, to leave the home and join the labor force. And the invention of the sewing machine not only made their work easier and faster, but it also demonstrated to the world that women could handle complex machinery (a fact that had not, apparently, been previously established).

So NAY worker exploitation, but YAY female independence.

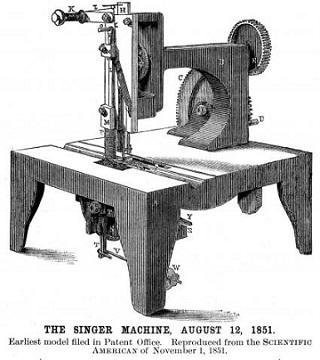

Elias Howe invented the first sewing machine in 1846, and it quickly revolutionized the production of clothing, not to mention the lives of women. Tweaks and improvements to the machine over the next decade by Howe, Isaac Singer, and others led to a booming sewing machine industry in the United States and beyond. Between 1854 and 1876, the Singer company was at the top of that industry, selling nearly 2 million machines, and that number doesn’t include sales from the 35 other manufacturers in the U.S. at the time.

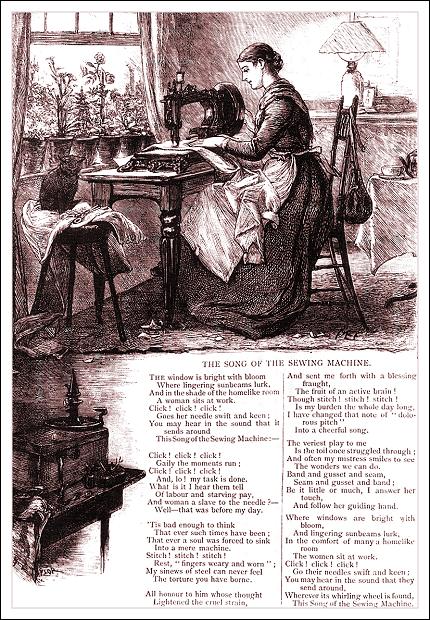

When sewing factories sprouted up across France, England, and the U.S., they liberated women from being “slaves” to the needle, since their stitchwork was formerly all done by hand. In contrast to Hood’s lament, there were poems and songs written to extol the freedom granted by the invention of the sewing machine. For instance, “The Song of the Sewing Machine,” a poem written by the enigmatic “S.E.G.” and published in Girl’s Own Paper, is told from the perspective of the machine itself and “gaily” describes its activity:*

Click! click! click!

Gaily the moments run;

Click! click! click!

And, lo! my task in done.

What is it I hear them tell

Of labour and starving pay,

And woman a slave to the needle?—

Well—that was before my day.

According to this song, the personified sewing machine inaugurated a new day that made women’s lives easier by freeing them from the laborious work of sewing by hand.

The Trouble With Treadles

But even with the increased technological ease, these women’s lives were not all wonder and joy. On the contrary, many textile workers began to complain of various ailments like fatigue, back pain, and even hemorrhages. The (male) physicians to whom these problems were reported—including Dr. J. Langdon Down, who became famous for his description and diagnosis of the condition now referred to as Down’s Syndrome—all pretty much agreed on the cause of such ailments. Was it the long work hours? the rapid pace of production? the poor ventilation combined with dust and cotton particles in the air?

No, no, no… It was female masturbation, duh!

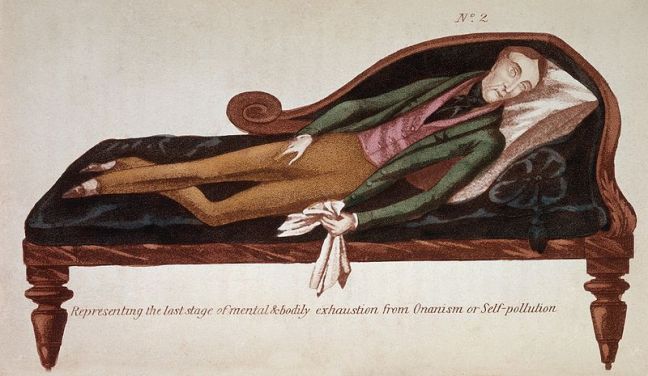

Part of broader 19th-century efforts to channel libidinous energy into more productive and supposedly less pathological directions, this diagnosis of excessive stimulation was a common answer to all kinds of health problems. The second half of the 19th century saw much scholarly discussion about energies, expenditure, and exhaustion in areas as seemingly diverse as steam engine technology and human psychology. Naturally, this interest was applied to the so-called vital forces of sexuality as well.

Whereas some physicians prescribed doses of vibration to relieve the symptoms of hysteria (sewing machines were not the only exciting invention of the mid-19th century!), the men of the textile industry and the doctors brought in to study the women were intent on putting a stop to this stimulating side effect of sewing. Langdon Down observed that the treadle action caused excessive blood flow to the nether regions that then left the women with a “diminished luster.” Charles Malchow warned that seamstresses could experience friction that might even lead to orgasm (oh my!) while working.

This was not strictly a physical issue; nay, it was a moral one. Dr. Eugène Guibout warned his fellow physicians (addressed as “Gentlemen”) of the moral dangers of “a machine that has the unhappy privilege of being doubly dangerous”: 1) it threatens physical health by requiring strength beyond a woman’s abilities, and 2) it threatens her moral health by fostering certain “habits.”

Now the Song of the Sewing Machine doesn’t seem so innocent. I can’t read this stanza with a straight face:

The veriest play to me

Is the toil once struggled through

And often my mistress smiles to see

The wonders we can do.

Band and gusset and seam,

Seam and gusset and band;

Be it little or much, I answer her touch,

And follow her guiding hand.

Smiles? Wonders? Touch? Her guiding hand?! That is one sexy sewing machine.

There wasn’t necessarily consensus about who or what was to blame for the “problem.” Some blamed the sewing machine itself as inherently dangerous. Others qualified the accusation, saying that a single treadle machine was fine but a double treadle machine (like the dirty French tend to use!) was asking for trouble. And still others saw no fault in the machinery and instead called out the women themselves: Dr. Emile Decaisne asserted, “Almost always I have located the cause for certain maneuvers and the excitations … in earlier habits, in moral perversion, or in individual physical problems.” In other words, the sewing machine can only excite women who are already perverts and are going out of their way to be excited.

I can’t help but think that, instead of getting real help for the detrimental effects of their labor, these women were getting shamed for the one part of their job that was pleasurable. And in an even bigger way, I wonder if this moment of male “experts” taking control of women’s habits is part of a larger narrative not just about the kinds of labor a woman’s body can do but about her bodily relation to that labor: these men stumbled upon an unspoken erotics in the repetitive activity of stitch work, and it was a feminine excess that they simply couldn’t abide.

So anyway, it’s the start of sewing season, and while I’ve got a slew of practical projects lined up, I’m going to take some time first to stitch up a piece to commemorate these women’s labors and their pleasures. (Don’t worry—I have an electric sewing machine, so I won’t have any hysterical side effects while I’m at it.)

[See the project inspired by this history in this Making It, Ourselves post!]

_ _ _ _ _ _

NOTES:

*Yes, I know there was a time when gaily just meant gaily. But it is a curious inclusion when one takes into account the mention by Krafft-Ebing in his notorious compendium Psychopathia Sexualis of a scholar who believed the use of a sewing machine was one of several telltale activities that might indicate lesbianism: “Coffignon … reports that this vice [“Lesbian love”] is, of late, quite the fashion,—partly owing to novels on the subject, and partly as a result of excessive work on sewing machines, the sleeping of female servants in the same bed, seduction in schools by depraved pupils, or seduction of daughters by perverse servants” (430).

FURTHER READING:

* Belofsky, Nathan. Strange Medicine: A Shocking History of Real Medical Practices Through the Ages

* Maines, Rachel. The Technology of Orgasm: “Hysteria,” the Vibrator, and Women’s Sexual Satisfaction

* Offen, Karen. “‘Powered by a Woman’s Foot’: A Documentary Introduction to the Sexual Politics of the Sewing Machine in Nineteenth-Century France”

* Roach, Mary. Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex

5 thoughts on “HISTORY PROJECT: The Immoral Rhythms of the Early Sewing Machine”